Werner Huber: “After I graduated, I realised that I had a huge number of opportunities available to me.”

- Alumni Portraits

- Architecture Alumni

Even as a child, Werner Huber was fascinated with building. As this fascination developed, he studied architecture at ETH. After a couple of years working as an architect and ETH assistant, Werner Huber decided to change tack; moving from a creator of architecture to an appraiser of architecture. He is now the editor of the magazine “Hochparterre”. His book “Architekturführer Zürich”, the first ever guide into the architecture of Zurich, was published this summer.

You are the editor of “Hochparterre” and the author of “Architekturführer Zürich”, which was published this summer. Who would you recommend this book to?

Anyone interested in Zurich: the city, its history and in particular its architectural history.

Of course, the main target audience of an architectural guide is architects. However, it was important to me to write a book that can be read and understood not just by experts but also ordinary people with an interest in the subject. This writing style reflects our work at external page “Hochparterre”; here too, we try to write in a way which is comprehensible to anyone interested in the content. In my external page architectural guide, I describe not only 5-star architecture, but I also look at other buildings that stand out in the city and which many people will not perhaps like when they first encounter them. Yet, these buildings are interesting enough for people to discover more about.

“Through my grandfather and my fascination with building, I just knew that I would become an architect.”Werner Huber

At the start of the 1990s, you graduated in architecture from ETH. Why did you decide on this course?

Even when I was a small boy, I was fascinated with building things. I built Lego houses and my drawings always had houses in them. Also, my grandfather was a bricklayer foreman and sometimes took me with him to building sites when I was staying with them. Interesting enough, at the start of the 1960s, he was even involved in construction of the first three buildings at Hönggerberg. So I never questioned what profession I would pursue later in life. Through my grandfather and my fascination with building, I just knew that I would become an architect. The only question that was not yet resolved was how to get there. I could either complete an apprenticeship and then go to technical school or I could attend the cantonal school and study at ETH. My grades at school were good enough so I went to ETH in 1985.

What did you do after graduated?

When I graduated in architecture in the spring of 1991, I knew that I wasn't the kind of person who would one day have their own architect’s office. So after graduating, I worked for a year as an architect in Switzerland before moving further east.

Just a couple of weeks before graduating, I visited Moscow on a group trip. I was bowled over and I fell under the spell of the huge city of Moscow. While working as an architect, I started to study Russian part time. In the spring of 1992, we undertook a study trip and I got to experience Moscow all over again. I was increasingly feeling myself pulled to the east so I put an ad in the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” newspaper stating “Young Swiss architect seeks job in Moscow”. And a company actually responded. Even though this company didn't appeal to me as an employer, I saw it as a golden opportunity: I knew I wanted to go to Moscow.

I seized the opportunity and moved to Moscow in the autumn of 1992. I stayed a total of two years. After three unsatisfactory months working for this company, which sensed a huge volume of business after the breakup of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the economy, but wasn't able to offer me a proper job, I resigned. But I stayed in Moscow, made contact with the architectural school and attended classes. My savings and occasional work kept me afloat. In those days, everything was fairly cheap and you could get by with little money and it was easy to get a residency permit.

“At some point, it became clear to me that I was actually more interested in the work I did in my spare time than my actual job.”Werner Huber

How did you come to be a journalist writing about architecture?

Back during my time at uni I had attended classes on the elective architectural critique course run by Benedikt Loderer, one of the co-founders of “Hochparterre”. So this was my first taste of the occupation. Ever since, now and again I have written short reports for say local papers.

While I was in Moscow and had a lot of spare time, I wrote for a Dutch architectural magazine a couple of times. Once I had returned to Switzerland in 1994, I took on a job as an assistant to the Spieker chair in architecture. During this time, I was heavily involved in architecture even if I didn’t practice it personally: I prepared study trips and seminar events and was engaged in architectonic topics, which the students were to work on during these events. After my time as an assistant, I spent another two years working as an architect, but I was always also writing on the side; sometimes for “Tages-Anzeiger”, and now and again even for “Hochparterre”. At some point, it became clear to me that I was actually more interested in the work I did in my spare time than my actual job. As luck would have it, there was a vacancy at “Hochparterre”. And this coming February, it will be twenty years since I joined the magazine.

How would you rate the architecture of Zurich?

On the whole, I would say that it is relatively “homogeneous”: nothing really stands out, either as being fabulous or terrible. Overall, Zurich’s architecture is of a high quality. The fact that here in Switzerland we haven't suffered from any wars over the last few centuries and so have escaped any major destruction certainly contributes to this homogeneity and also continuity. With the exception of Geneva, I feel that Zurich is the only Swiss city with the atmosphere of a metropolis. Even if internationally speaking, Zurich is of course relatively small.

There is only little disruption in Zurich. Everything seems to be complete, everything is attractive and positive. You could say that Zurich is rather boring. Moscow, Warsaw or even Berlin are cities shaped much more by disruption and urban conflicts. Zurich has very little, if any, of this. Sometimes this kind of disruption is good for a city. Even if at first glance things are perhaps destroyed, which can be annoying.

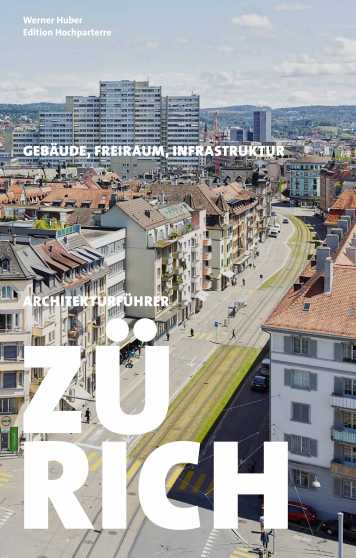

Architekturführer Zürich

The "Architekturführer Zürich" presents 1200 buildings including associated texts, pictures and many previously unpublished drawings. The architecture guide not only lines up the well-known and beloved architectural jewels, but also depicts buildings that are difficult to assimilate in the context of urban structures.

The book can be ordered at the external page online shop of Hochparterre.

How do you think we should assess architecture?

Well, there are a huge number of different factors that need to be taken into account. And that’s what I find so exciting about my profession. One factor is functionality: a construction job usually has to fulfil a purpose and is therefore assigned a function. Another important aspect is space. Architecture shouldn’t just produce usable areas, but also create spaces. The way in which spaces interact, the dimensions of these spaces and the areas they cover are hugely important. Then, there’s the choice of material and colours and of course as things progress, sustainability aspects too. The difficulty with this last aspect is that sustainability mustn't be pitted against the other factors. I often hear people saying that the requirements are too restricting and so compromises had to be made in terms of other aspects. I can't accept this argument. The requirements are laid down and have to met, it is the job of every architect to work within the framework of these requirements. If this isn’t done, the job isn't complete.

What advice would you like to give to the current cohort of students of architecture?

I think it’s important to keep expanding your horizons. When I look back on my time at uni, I realise that architecture is a topic of incredible breadth and therefore touches on many different aspects of and in life. It’s a career with which you can choose from very different jobs. After I graduated, I realised that I had a huge number of opportunities available to me. So I hope that all students of architecture tap into these opportunities and, even during their time at uni, come to realise how they can use the knowledge they acquire later in life.